From The San Francisco Chronicle

Nation's first all-transgender gospel choir raises its voices to praise God and lift their own feelings of self-love and dignity

Rona Marech, Chronicle Staff Writer

Sunday, April 18, 2004

At first, Bobbi Jean Baker, a big-voiced, loud-clapping, ex-convict Tennesseean with deep roots in the Baptist Church, was skeptical of the new gospel choir at San Francisco's City of Refuge United Church of Christ. Who's to say they could sing?

But a friend dragged her to a rehearsal, and sitting in the audience, she thought, "Mmmm -- they got a little beat about themselves." The next time she stopped by, she found herself singing along when a member motioned to her, saying, "Oh, precious, you need to come up here."

So Baker, who used to only set out in female clothing after dark, quit hiding and began raising her voice. For the last two years, she has been a loud and proud member of Transcendence Gospel Choir, the very first all- transgender choir in the nation.

"I'm human and guess what? I want to lift up the name of Jesus. And if I want to sing, I have that right," said Baker, who was born male but has lived as a woman for the last three years. "I always knew God loved me, but I always had trouble with the lifestyle: How can I say I worship Him and have this lifestyle? Until I come to find out that you can have your spirituality and your lifestyle altogether.

"God said, 'whosoever,' " she said. "That means transgender people."

Transcendence Gospel Choir follows in the footsteps of gay and lesbian choirs around the country, which -- for 25 years -- have been using music to gain acceptance and visibility, express pride and offer hope to the hopeless. In just three years, the transgender choir has grown from a ragtag assemblage unsure of how to use their voices into a gospel powerhouse with fans and concerts and a walloping sound.

"If any message of any song I sing helps someone get out of their inner locked-up cage, that's what I'm for," Baker said, "because it took me a while to get free."

Last year, after the group recorded its first CD, "Whosoever Believes," Zwazzi Sowo, a fellow member of City of Refuge, bought nearly a dozen copies to give as gifts to family members -- straight and gay alike. When Sowo's brother died, she brought a CD to his grieving widow, a religious African Methodist. The music will heal your heart, said Sowo, never explaining the "trans" part of "transcendence." Her conservative sister-in-law learned every song on the CD and later asked Sowo to thank the singers from her church. Sowo had to smile.

"For them to take a stance and just to claim who they are in song is so powerful," Sowo said. "When you're hurt or marginalized, a lot of times what you do is shrink and try not to be seen so you don't hurt so much. But their music is about expansion and stepping into it. It's about growth. ... It's here to heal the world."

Putting together gospel music and transgender people -- anyone whose gender identity is different from the one assigned at birth -- might not seem like the most obvious route to world healing. Founder and co-director Ashley Moore, 37, a respected local record producer and musician, was racked with doubt when "God burst this thing in my mind."

"Where will we sing?" she recounted asking herself. "Would people stop laughing long enough to listen?

"You know how the queer community is. They don't want to hear anybody talking about God. They have too many wounds from Bible abuse and queer bashing," Moore said. "And then the Christians who have bought in to the whole mistranslation of the Bible think, 'What is this? Queers are singing gospel?' "

Well, yes.

Moore, who has wide blue eyes and is always perfectly made up, said shame about her identity had led her to years of substance abuse and depression, and she was determined to use music to spread the word that it was possible to be transgender and self-loving and a person of faith.

She asked Yvonne Evans, who had grown up in the church and is known to be a strict and devoted choir leader, to be the director. Evans understood little about transgender people -- at the time, she thought they were all "showgirls" -- but she agreed anyway. So early in 2001, Moore hung up flyers advertising the first rehearsal. Six people showed up.

"Six people who really couldn't sing. I'm going to be honest with you. They came from everywhere. From the street. They were homeless, prostitutes," Evans said.

"They all wanted to do falsetto -- badly,'' Moore said.

"Real bad," said Evans.

Members of the choir are in various stages of transition from one gender to the other, which means some have gone through hormonal or surgical changes; some voices have changed because of hormone treatment. Moore and Evans just wanted singers to use their natural voices -- even if the register was higher or lower than typical male or female voices. Moore repeated advice she had once gotten: "Just sing from your heart and let your spirit speak."

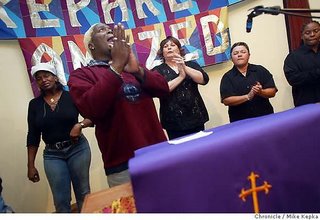

Eventually, some new members joined and others were given a gentle nudge out. The choir -- a diverse group of mostly African Americans, some Latinos and a couple whites -- has now grown to 18 people. They pray in a huddle before every performance, then go on stage and rock the house. When the spirit so moves them -- and it frequently does -- they clap and bow, throw back their heads and raise their hands up high.

"The Holy Spirit comes through us," Moore said.

Kathleen McGuire, the conductor of the San Francisco Gay Men's Chorus, recalled the first time she saw the choir perform. "The sound this small number of people produced was just amazing," she said. "Most of all, what struck me was the personal conviction on their faces."

The choir performed at events from the grand opening of the LGBT Community Center in San Francisco to a 2003 LGBT interfaith conference in Philadelphia.

In 2003, the choir sang in Minneapolis at the general senate meeting of the United Church of Christ. Although the church is not predominantly gay and lesbian, it is a "predominantly justice" church, said the Rev. Dr. Yvette Flunder, the City of Refuge pastor. Following the performance, the senate voted to expand its ministries to transgender communities.

Last year, Moore -- who has worked on CDs by performers from singer Rhiannon to rockers Third Eye Blind -- donated her studio and about $20,000 worth of her time to produce and engineer the choir's CD. So far, they have sold 900 of the 1,000 copies they made.

Transcendence Gospel Choir is part of what some consider a movement.

The San Francisco Gay Men's Chorus, one of the country's first gay choruses, made its first public appearance the day that Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk were assassinated in 1978. They had been scheduled to rehearse, but instead, the chorus went to City Hall and sang a hastily prepared hymn.

"Here was a group of people that felt marginalized, that was looking for a way that they could stand up and be visible as a group in a way that was safe," McGuire said.

Twenty-five years later, as the transgender community goes through some of the same battles for recognition and acceptance, Transcendence has stepped up as pioneers and "cultural warriors," she said. She was so inspired by the choir that she organized a program of gospel, spirituals and Motown music and invited Transcendence to join her choir in concerts Saturday night and tonight at Mission High School.

For many singers in Transcendence, the choir is "family."

"I feel more complete than I had before in my life," said Jerimyah D'Luv. "Now I feel I'm a part of, instead of feeling like an outsider."

Bobbi Jean Baker, a former crack addict who completed a 23-year sentence for robbery and second-degree murder in 2000, said that after joining the choir, "I went from being a nobody to being a somebody."

On the CD, Baker is the soloist on the song "I Almost Let Go," which she sees as a personal anthem.

"I felt like I just couldn't take life anymore," the lyrics go. "But God held me close/so I wouldn't let go."

"Transcendence opened my eyes to a whole new gamut of life," Baker said. "I saw people, and some looked just like me. They had similar experiences, and they were living as to who they are."

Becoming more spiritual helped Baker, who has nine brothers and six sisters, reconnect with her family. Most of her siblings bought the CD. Her oldest sister refused to speak to her after her gender transition, but recently, they started talking, and she invited Baker to her daughter's wedding.

"I'm going," Baker said, "as who I am."

For more information about Transcendence visit their website at:

http://www.tgchoir.org/